We artists can be happy just having freedom and being able to express ourselves

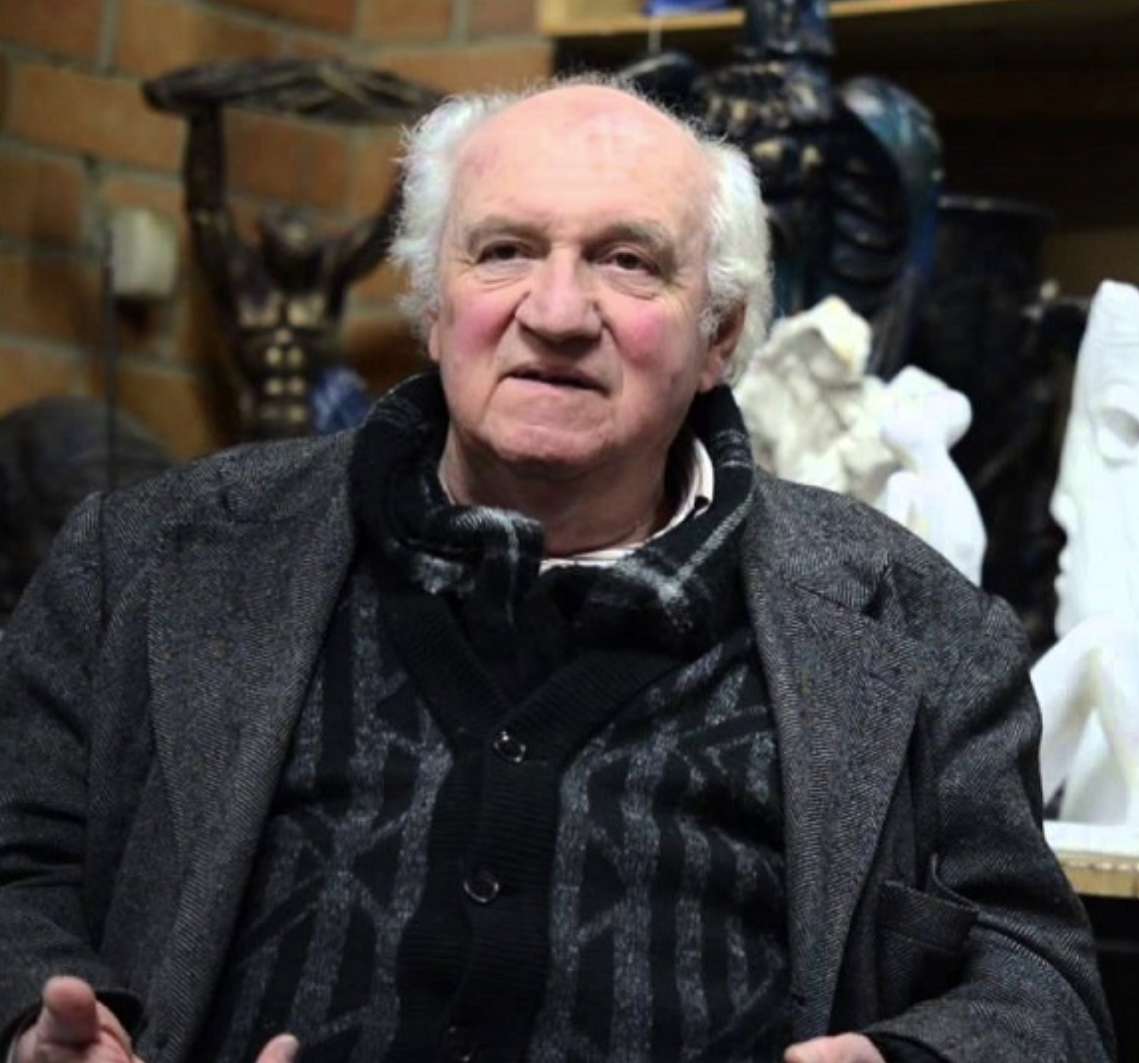

The painter and sculptor Ruv Nemiro may be one of the most highly admired unknown artists in Australia. That he was a famous artist in Uzbekistan, his country of birth, that he was part of a select group of Soviet artists who were allowed to interact with the global art world, and that he was a much sought after figure among other artists in his own lifetime, are not facts that are widely known in his adopted country. While it is relatively easy to find articles about him in foreign art journals, there is virtually nothing written in English about him.

Ruv Nemiro was born in 1937 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and studied at the Uzbekistan Institute of Art from 1952-57 completing a post graduate degree in Fine Art at Leningrad (St Petersburg) in 1961.

During his lifetime he created significant sculptures, both in quality and size, in the former USSR, mainly in the Uzbekistan region. Nemiro’s statues were highly regarded and he was commissioned to create towering works for palaces and public spaces.

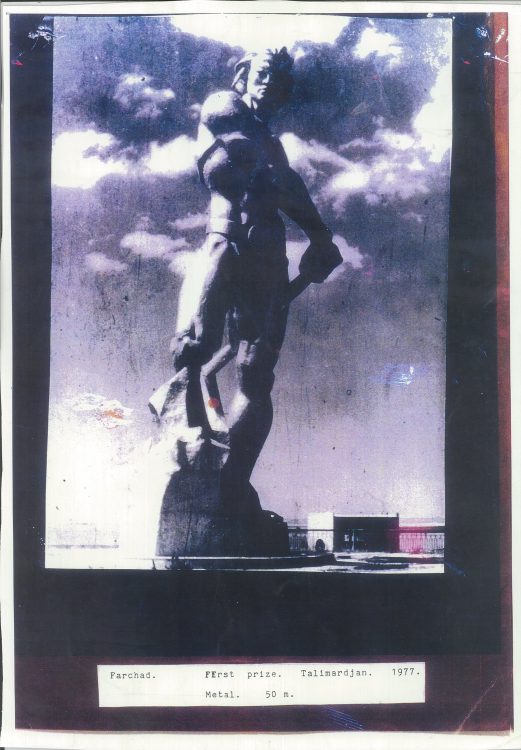

He was the designer and creator of the statue of Farhad in Tashkent, the capital city of Uzbekistan. For the people of Uzbekistan, this statue has the same level of fame that the Statue of Liberty has for Americans. Just as the Statue of Liberty stands for an idea that represents the United States itself, the statue of Farhad represents a legend and a motif that is integral to the cultural being of Uzbeks. Farhad brought water, and life, to the city and to the people, and sacrificed himself for love.

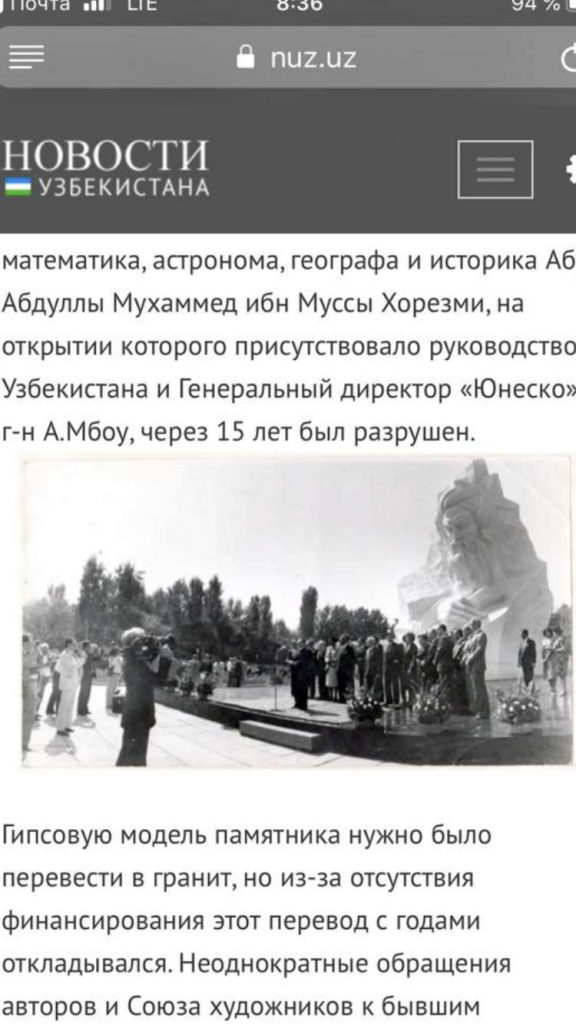

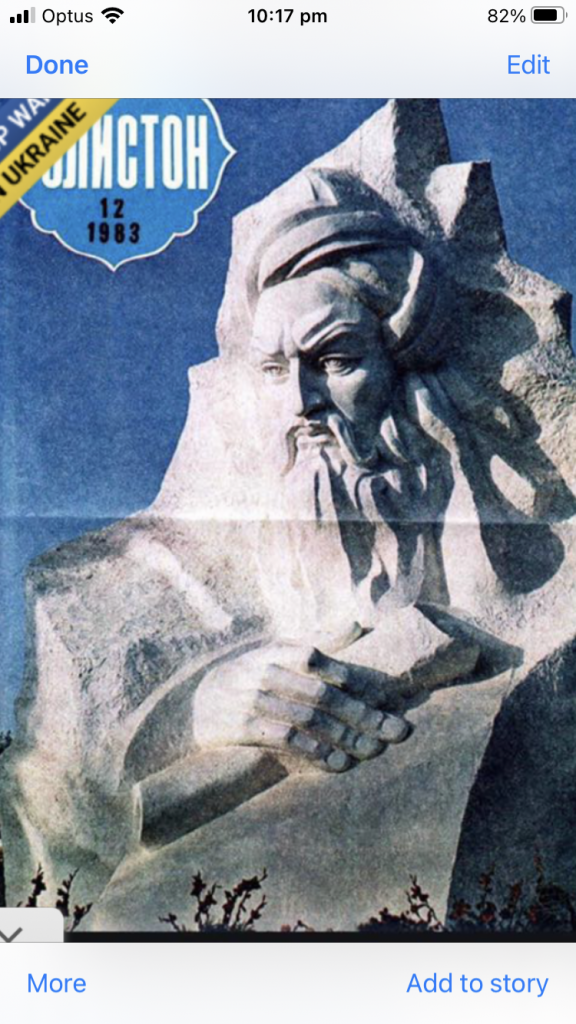

Nemiro’s sculpture of Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (780 – c. 850), or al-Khwarizmi, a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, known as the Father of Algebra, was opened by the President of UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) in Tashkent in the early 1990’s, not long after Nemiro had departed for Australia. This monument, now under reconstruction, was left in plaster and never transferred to granite, as Nemiro was no longer there to complete it. It has suffered much from the effects of weather, but is so highly valued that efforts are underway to bring it back to its original form.

Throughout much of the history of the USSR (1922 – 1991) it was virtually impossible for citizens of Soviet Union to move or travel abroad. However, while closely monitored by the KGB at all times, Nemiro was one of a select group of artists who were allowed contact with foreign artists. Such was the importance of his work and his influence, he was even permitted several trips abroad in order to absorb and contribute art ideas and inspiration in the wider world.

In the early 1970’s Nemiro was one of a small group of Soviet artists who visited Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) in his studio in Paris. Picasso was interested in the Soviet Union and in communist ideas and forms of expression. While conversations were both monitored and directed by KGB agents, Nemiro was able to take a risk and told Picasso that he’d love to sculpt his portrait. This he did, later sending the sculpture to Picasso with a note “for my favourite artist.” However, it is not known if this significant piece of Nemiro’s work ever made it out of the Soviet Union, as all international communications were intercepted and he did not receive a reply from Picasso.

In 1976 Nemiro was again permitted to travel with a small group of Soviet sculptors and painters to London where they met with British Sculptor Henry Moore (1898 – 1986). Moore was a great symbol of Western modern art for these Soviet artists and there was much sharing of ideas and experiences in these meetings. It was rare for Western artists to have the opportunity to meet with peers from the USSR, and the participants would be well prepared with photos, slides and materials that they could study and workshop together.

The Belarusian-French artist Marc Chagall (1887 – 1985) was another of the influences in Nemiro’s life, and Chagall was a frequent visitor to many parts of the Soviet Union. Nemiro met with Chagall a number of times at events such as an invitation to the Hermitage in St Petersburg to mingle with well-known artists from all over the USSR and to meet with Chagall who was much feted by Soviet artists during his travels.

Nemiro was the recipient of a number of prizes and major public commissions in Europe and was a Professor at the University of Uzbekistan for over a decade. Many of his students are still living and remember him fondly. In some respects Nemiro lead an enviable life; his clients being predominately royalty and political leaders, but in other respects, like so many of his generation, he was buffeted by the tides of war and political strife that ravaged Eastern Europe throughout the twentieth century; culminating in a move to Australia in 1990. He became a citizen in 1992.

By the time Nemiro reached Australia, he had over thirty years of experience in monumental sculpture, for which he won international and national awards in the former USSR, including winning the National Public Art Competition eight times. His monuments and other commissions are found in Uzbekistan and Russia, and his works have been exhibited and collected throughout Europe, Asia, America and Australia. Nemiro was also the designer of many buildings and landmarks in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and the designer of palaces, restaurants and stadiums in Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Australia.

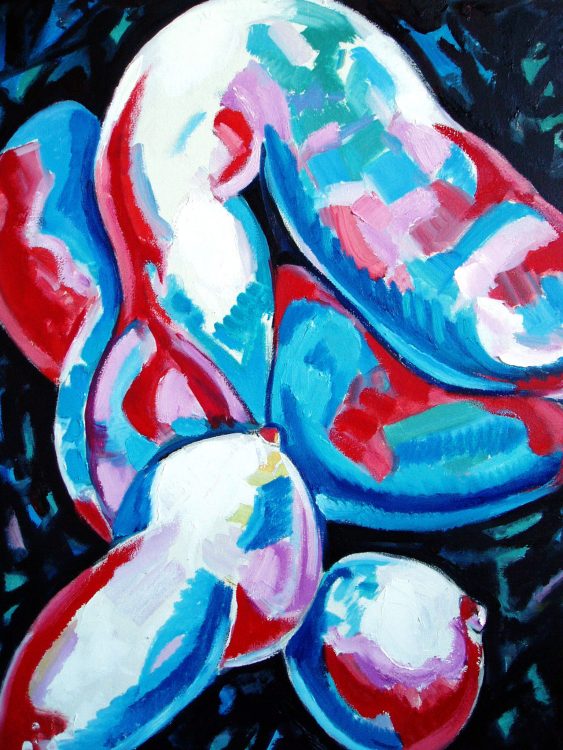

In addition to his sculptures and monuments, Nemiro was a prolific painter exploring a variety of different techniques and genres. In later life he would spend much time in his studio in Australia, deriving joy from the process of expressing himself through colour and experimenting with abstract styles heavily influenced by Cubism.

Not long before he died Nemiro reflected on his life and his work, saying “I dedicate my art to my friends, those that I was fortunate to have come across and those that I yet have to meet in my life. To the friends who are with us today and to those who have gone forever remaining in my memory and heart. I dedicate it to my dear friends, with whom I have spent my best years”.

His son, the artist Alex Nemirovsky, says “it was my big luck to have a teacher like him from an early stage. Father was one of just a few sculptors in the country to have such big government commissions during those times, and I was so lucky to have him as my first mentor and best friend. He was truly a talented and generous artist”.

Ruv Nemiro died in 2019.

Some of Nemiro’s works are outlined below:

Designer and creator of the 50 Foot sculpture of Uzbek National Legendary Hero – Farhad, in Uzbekistan. The Tashkent reservoir Charvak is guarded by Nemiro’s statue of Farhad, a hero who once changed the course of the river for the sake of great love. Inspired by the poem “Farhad and Shirin”, written by the great Uzbek poet Alisher Navoi, the sculpture is based on the Iranian folk legend about the hero Farhad and the princess Shirin, for whose hand the latter tried to crush the rock and create a reservoir for the capital.

The statue of al-Khwarizmi was opened by the President of UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) in Tashkent in the early 1990’s, not long after Nemiro had departed for Australia. This monument, now under reconstruction, was left in plaster and never transferred to granite, as Nemiro was no longer there to complete it. It has suffered much from the effects of weather, but is so highly valued that efforts are underway to bring it back to its original form.

Nemiro’s sculpture of Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (780 – c. 850), or al-Khwarizmi, a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, known as the Father of Algebra.

Symbolic expression for a monument titled “Australia”, 90 x 90 x 27 cm. The larger monument was not built, but this sculpture in bronze and granite has been exhibited in multiple galleries.

Sculpture titled “Girlfriend of Picasso”, mixed media, 43 x 18 x 23 cm.

Black Torso, ceramic, 70 x 18 x14 cm

Cardinal and Spirit, ceramic, 54 x 14 x 14 cm

Dream, ceramic, 3 x 18 x 18 cm

Figure, ceramic, 30 x 15 x 15cm

Lovers, ceramic, 25 x16 x 9 cm

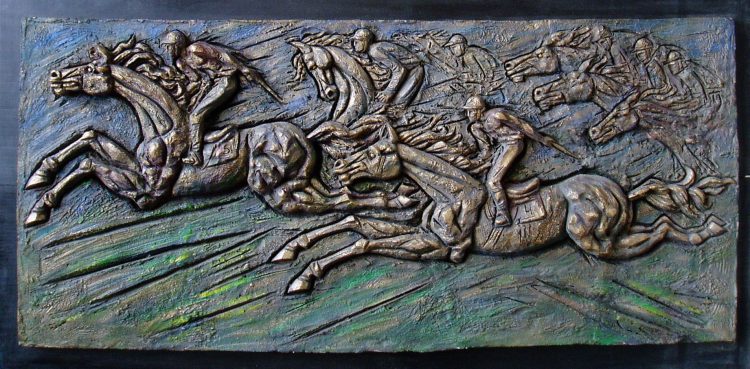

Melbourne Cup, relief, 130 x 60 cm

Memory of Modigliani, relief, 32 x 50 cm

Romeo and Juliet, vase, 70 x 30 x 25 cm

Woman and Pigeon, ceramic, 22 x 15 x 10 cm

Farchad. First prize. Talimardjan. 1977. Metal. 50 metres.

This portrait of Pablo Picasso was made by Nemiro in Australia, years after the original that he made and tried to send to Picasso in the early 1970’s. He did it from memory and his son Alex believes it is a good likeness of the original. Nemiro had said that Picasso’s look was arresting and that he wanted to capture this in the portrait.

The Lady of St Kilda, Melbourne, Australia was designed and created by Ruv Nemiro’s son, Alex Nemirovsky. Alex credits his father not only for all the metal structures and metal work, but for being his artistic mentor and best friend. This much treasured art work stands as a legacy of an enduring partnership.

Conversations (II), oil on canvas, 90 x70 cm

In the Art Studio, oil on canvas, 80 x 50 cm

Matisse in the Studio, oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm

Woman Nude, oil on canvas, 90 x7 0cm

Volcano, oil on canvas, 120 x100 cm